Formal Irrigation Schemes

Formal irrigation

schemes increase water security. Such security really is a matter of life or

death in arid and semiarid climates such as those throughout Africa, where local

populations depend upon rivers as their primary source of water for both

domestic and agricultural use. Such schemes more often than not involve

building large dams. There is potential for damming with regulated releases to achieve,

or at least increase, food security (Lele and Subramanian, 1989). There are of

course some advantages to such schemes:

1. Formal

irrigation provides for year-round crop production in arid areas. The water crisis in

Africa means that food security is compromised, especially during the dry

season. Formal irrigation schemes

mean that farmers know exactly how much water they will receive and are able to

plan for how best to use it to maximize crop yields.

2. Both upstream and downstream

communities can benefit from formal irrigation. Formal irrigation schemes are overseen

by either private or state-ran organisations who can monitor both groundwater

levels and the amount of water held in the dams. Such organisations have the

ability to fix any potential problems, such as technical faults, as well as

communicate with both each other and the public to make sure every stakeholders

needs are best met.

However, whilst formal schemes for increasing the irrigation of

croplands may seem a no-brainer, they may have detrimental effects on the

wetlands. It is argued that many African river floodplains are getting smaller as

the result of water management activities such as irrigation schemes (Barbier and Thompson, 1998). A paper by Thompson and Hollis (1995) essentially undertook a cost-benefit

analysis of fully implementing KRIP, a large formal irrigation scheme. The

Nigerian government invested heavily in the project due to the failure of independent

farmers to meet the fast-growing demand for agricultural commodities in the

1970s. The project hoped to increase the potential of Nigeria’s agricultural sector.

KRIP

was established by the Kano state government, who proposed a development of

approximately 62,000 ha of agricultural cropland which would be formally (and

intensively) irrigated using water from the Tiga dam, which is on the Hadejia River.

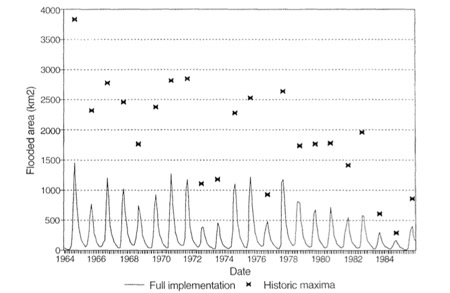

A model using observed river flow data was used to predict

the impact that abstracting water from the Hadejia-Jama’are river basin for use

in the irrigation scheme would have on the surrounding wetlands. Not only did

the model show that KRIP would reduce the flood extent of the wetlands, but the irrigation scheme would also mean that the volume of groundwater

held in aquifers beneath the wetlands would be reduced. As aforementioned in one

of my previous posts, groundwater has the potential to overcome the challenge

of drought across Africa. Hence, a reduction in groundwater levels is not a favorable

consequence.

|

| Figure 2: The observed maximum flood extent of the wetlands compared to the modelled flood extent if KRIP was fully implemented |

- Poor maintenance. Despite the management committees in place to deal with any technical faults, poor African economies often mean that the initial Implementation of schemes is haphazardly and poorly done. Furthermore, high corruption often means that broken pipelines and such will not be fixed without bribes. In the case of the KRIP project, conflicting interests at management level meant that farms were not properly developed for irrigation production, undermining the realization of projected crop yields.

- Watering preferences of crops is not always considered. Large scale irrigation schemes such as KRIP cannot always meet the needs of individual farmers and their crops. The management authorities, who are in charge of running the schemes and deciding how much land is to be irrigated and how intensively, often have little knowledge of farming practices. More irrigation may sound beneficial in dry croplands, but the crops being grown may actually require little water and so ecessive watering may result in crop failure.

- Potential for conflict with downstream settlements. The completion of the Tiga Dam coincided with a persistent drought in the region during the mid-1970s. Whilst the scheme meant that water security was somewhat increased during the drought due to releases from the dam, it also led to conflict between upstream and downstream settlements. Upstream farmers may overly exploit the water resource, particularly in times of drought, and downstream settlements may receive less than they need to sustain their crop yields.

Comments

Post a Comment